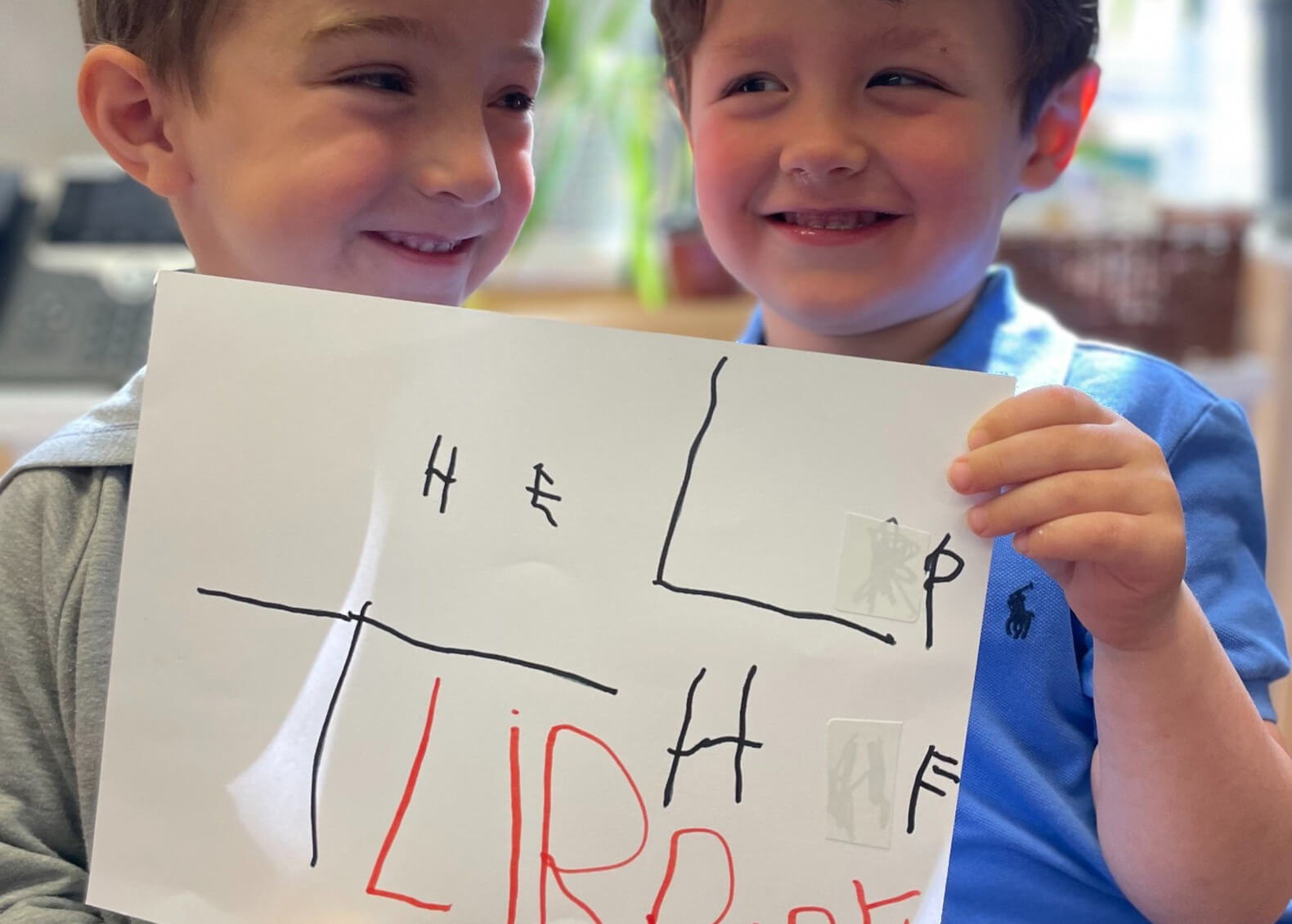

We wanted to take an opportunity to share a quick recap about power play, big bodied play, and rough and tumble play: What is it? What isn’t it? Why is it important? What can you do to support it at home that feels right for your family?

What is it? What isn’t it?

Power Play

Play where themes of power are explored through relationships (ie. “naughty baby and grown ups,” “villains and superheroes”) , roles (ie. big animals like cheetahs or royalty like queens), stories (ie. jail and trapping, alive/dead), and iconography that culturally represent power (ie. weapons, wands).

Big Bodied Play

Large motor physical activity with or without contact, with or without play equipment. This might include rolling, jumping, falling, tumbling, and sliding.

Rough & Tumble Play

Frank M. Carlson wrote in an article Rough Play: “As children approach the pre-school years, these very physical ways of interacting and learning begin to follow a predictable pattern of unique characteristics: running, chasing, wrestling, open-palm tagging, swinging around, and fall to the ground–often on top of each other.” Play fighting and wrestling is one of the most nuanced and sophisticated forms of rough and tumble play that both teaches and requires children to use tools for perceiving, inferring, and decoding signals and nonverbal communication.

“Are you playing the game?”

Power play, big body play, and rough and tumble play are all kinds of … PLAY! Children are learning HOW to play this way, just like they are learning how to play pretend. This is why grown ups can play a role in supporting this play, and knowing when to recognize when it is play, and when it is NOT play.

When is it play?

Fun

Physically secure

Emotionally secure

Fulfilling positive needs or goals for the individual and group

Developmentally appropriate

There is a rhythm, like a dance, and children pause and check in with each other

There is often rules, scripts, and games

When is it NOT play?

Unwilling or unwelcome participation

Physically unsafe

Emotionally unsafe

Rooted in anger, aggression, or negative intention

Violence

There is not a give and take, call and response “flow”

Why is it important?

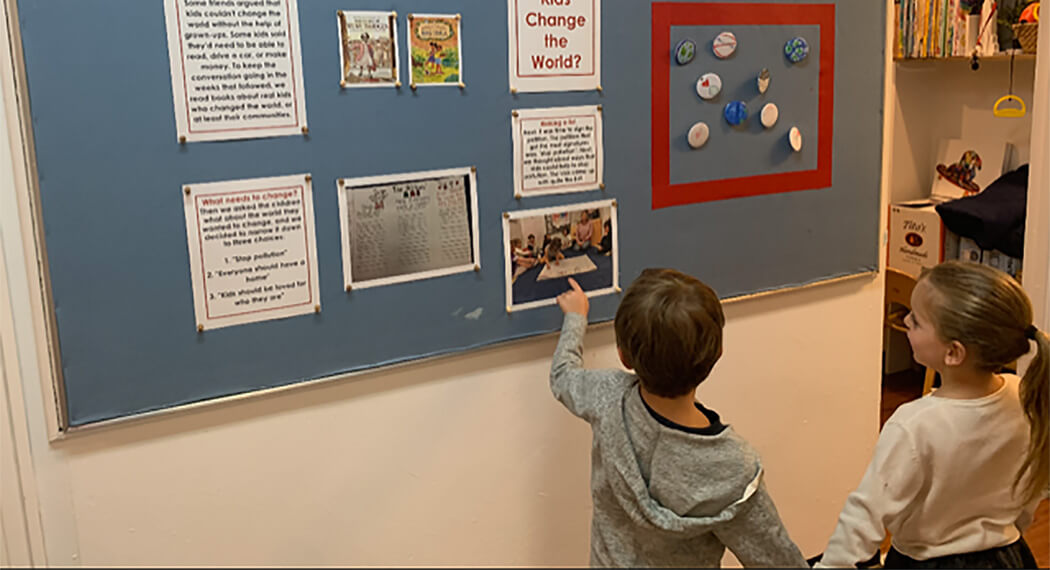

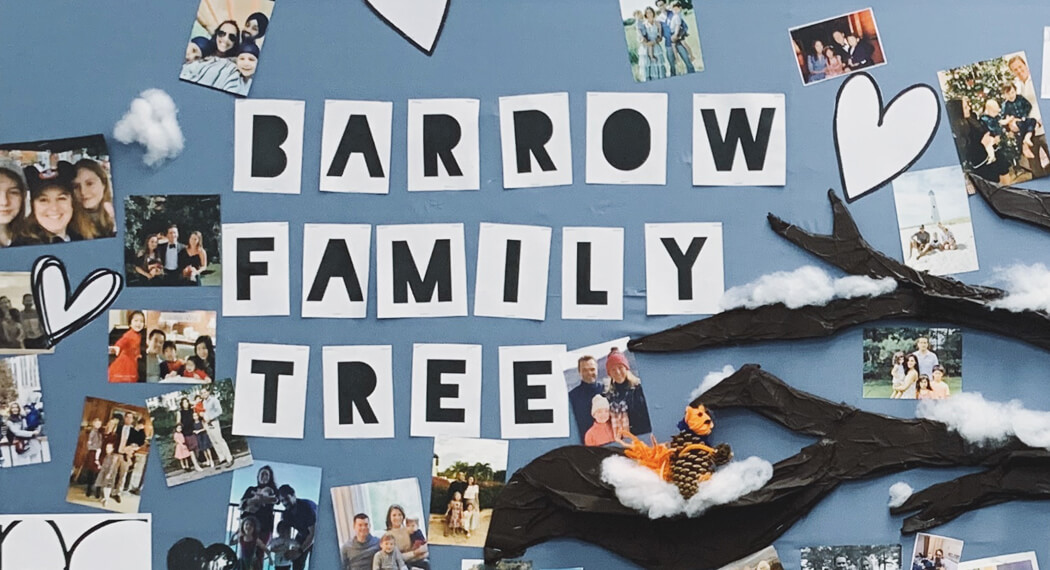

A part of our Barrow mission statement emphasizes that our curriculum nurtures children’s growing sense of identity,agency, and belonging. As educators, we believe that at school, power play, big body play, and rough and tumble play, when supported mindfully, can greatly contribute towards these goals.

Bodies are vehicles for establishing belonging. From a very young age children use their bodies to learn. It makes sense that in a 3s/4s year defined by relationships, the child’s relationship with his or her body evolves to include others. Now, children begin to understand their own limits and capacities and so reach out. At three and four, it is developmentally typical to see a lot of what is often classified as power, big body, and rough & tumble play as a tool for learning.

Children build a range of skills representing every domain while playing in these ways. For example:

Physical skills: how their bodies move and how to control their movements

Language skills: reading body signals and nonverbal communication, decoding symbols, cultural norms and cues

Social-emotional skills: turn taking, role switching, negotiating, and developing and maintaining friendships, language of consent, emotional regulation, processing feelings and concepts of identity

What can I do to support this play at home that feels right for my family?

We know that based on a variety of factors, people have differing stances about how to manage this play; a kind of play that can sometimes feel confusing or unsettling to adults. Here are some ideas for approaching risky play at home:

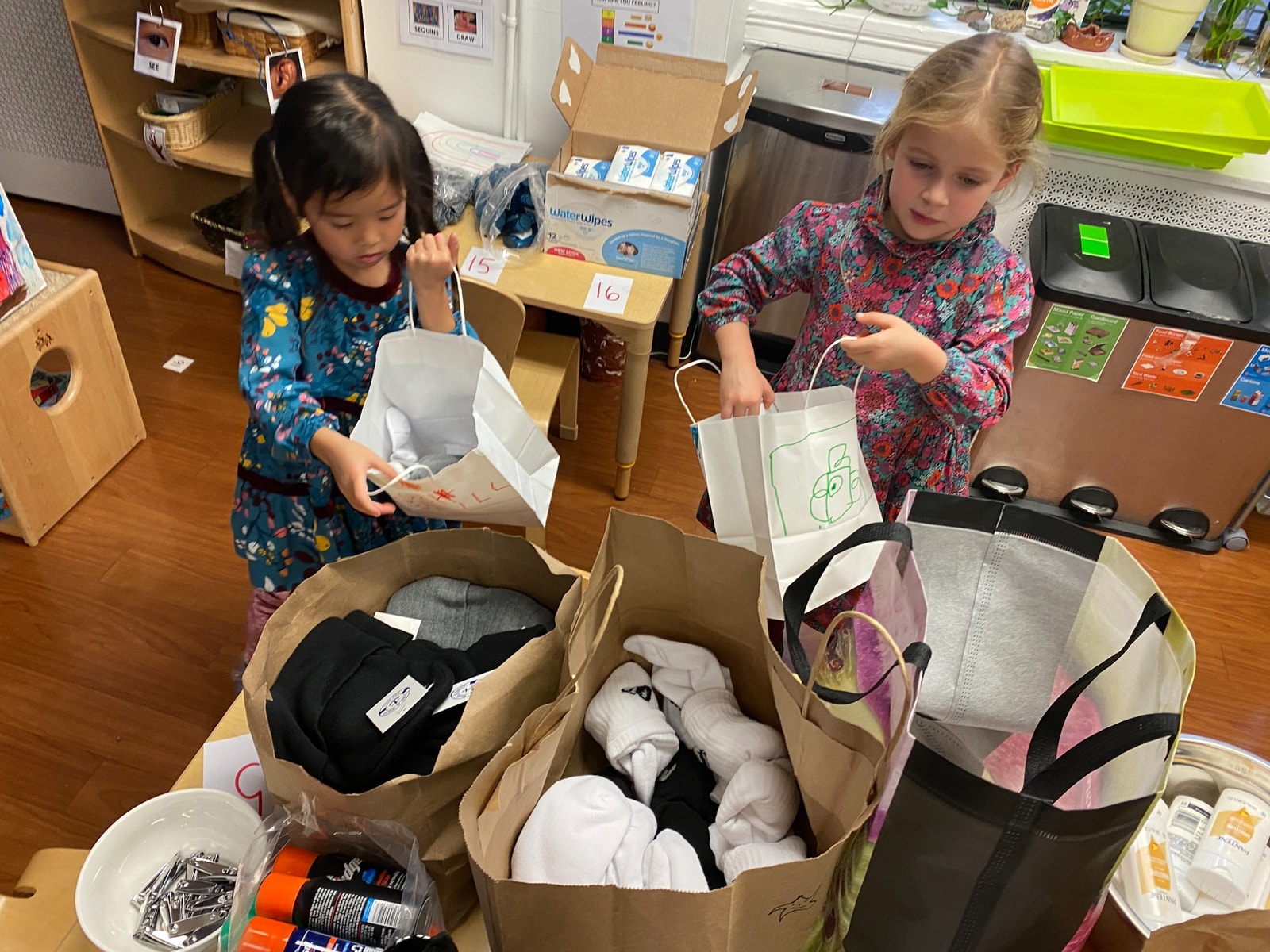

Home-School Connection

Inquire

Even if your child has a lower threshold for physical or power play, it is more than likely that they are observing or questioning other children’s actions. With all children, asking for context is an important next step for any observations or ideas they share both inside and outside of school. Asking open-ended questions like, “Was that part of a game?” “What did you do?” “What did you say?” “What did your friend say?” help form a full picture of an event. You might have a very clear idea of what your child is describing, but hearing their version of a story provides invaluable insight into how they are thinking about and processing an event, action, or decision.

These are also moments that allow us to support children’s development of empathy. Asking questions that require them to think about the other child(ren) involved in the play encourages them to think about perspectives other than their own. Questions such as, “How do you think they were feeling?” or “What do you think they were trying to do?” model for them the importance of considering things from another view point, while also potentially offering additional context to understand how the play evolved.

And, please don’t hesitate to inquire with your teachers, too! When a story feels muddy or doesn’t quite add up please reach out so that they might offer more insight. We are all part of a team with the shared goal of fostering compassionate and empathic individuals.

Empower

With this context, you are much better prepared to empower your child as an agent of change in our community. At home, you can talk with your child about how to advocate for themself and for others. Positioning your children to be proactive and view themselves as capable in these moments sets them up to be able to enter into and navigate a wide range of social situations.

Home Play: “BOAT”

While we have the space and resources to support all play styles in school you may have different limits at home. At this age, children are able to understand different expectations based on environment. For instance, we often discuss how “in school the elevator buttons are a teacher job and the rules might different when you are with your grown up.” Therefore, you may use any selection of approaches or techniques in supporting physical play in your home. If you want to try on some of this play at home, consider the following:

- Baseline – What are your personal, family, cultural, and/or societal values related to power, risk taking, physical play? What’s your child’s temperament? What’s your temperament? Just as children have different thresholds for physical play we also recognize that adults do as well.

- Observe – What is your child doing or not doing in this play? How are they feeling? What does their body language tell you? How are you feeling as you observe or play along?

- Assess – Think about the time and place for risky play. When is a good time and where is a good place to play this kind of game? Preview with children the agreements and rules of the game ahead of time.

- Teach – It’s time to play! You can watch from the side and be a “sportscaster,” narrating what you see happening and stepping in if you need to help pause the play to go over safety rules. OR you can be a playmate. Using the language of the game or pretend play world can help you shape the game so it fits with your values and boundaries.