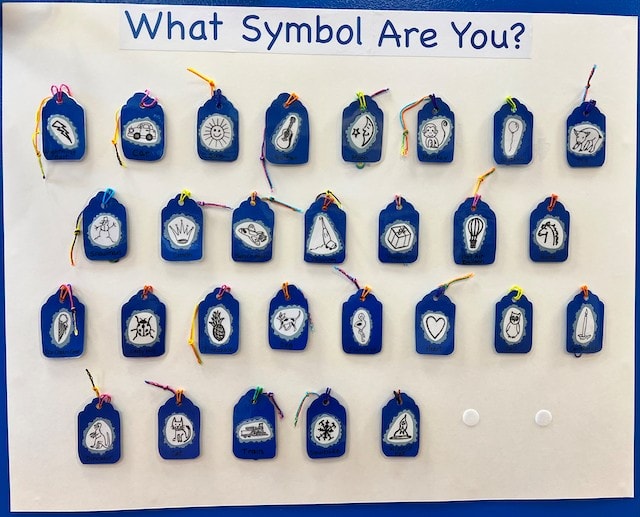

As you have undoubtedly noticed, your children’s names in the Blue Room are represented in a slightly atypical way: each name is accompanied by a small pictorial symbol. But what are these symbols for, and why are they there? Let’s explore how this might be experienced from the child’s perspective.

Imagine 4-year-old Cate, who cannot yet recognize her name. The world around her is filled with symbols, some familiar, but most not. When Cate enters the Blue Room, she chooses the otter as her symbol. She loves otters, so the choice feels natural. Every day, she sees the otter on various items and immediately knows they belong to her. Next to the otter are letters that are starting to make sense to her. She doesn’t know all the letters yet, but she quickly realizes that the four letters beside the otter — C, A, T, and E — also represent her and mark these things as hers. Before long, she can recognize those letters on their own, independent of the otter, because they now hold meaning to her. Just like that, she has learned to read her name.

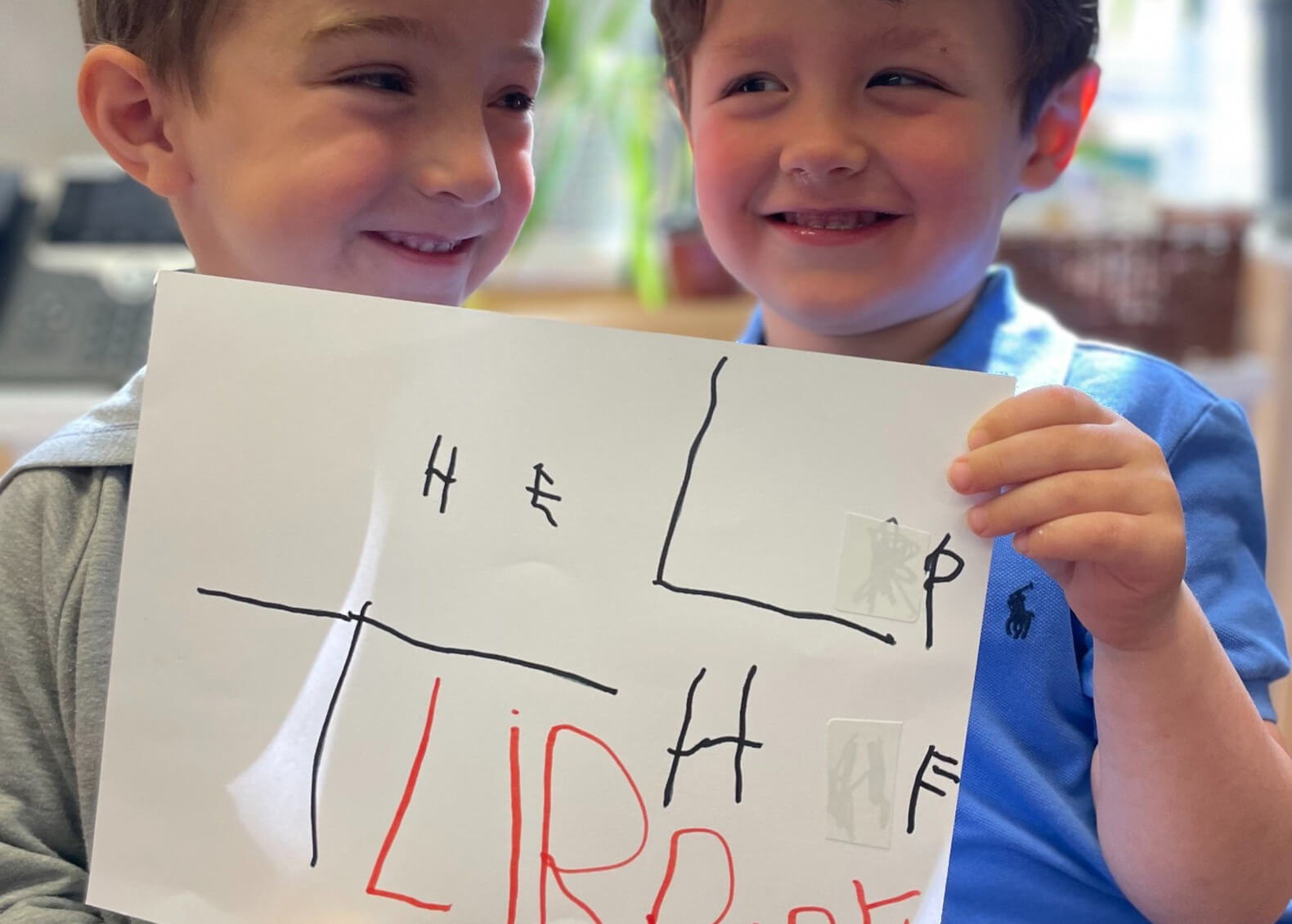

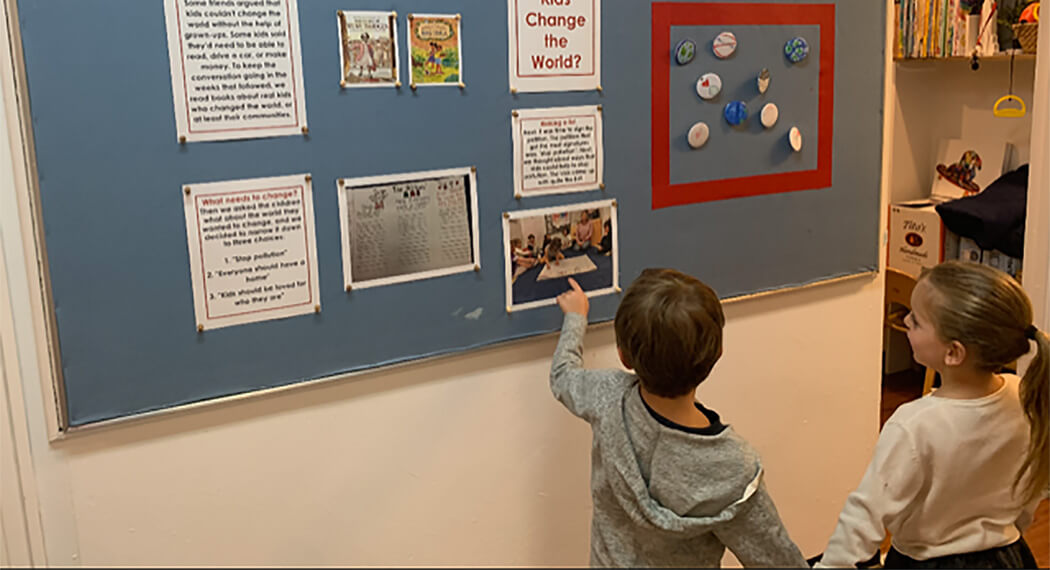

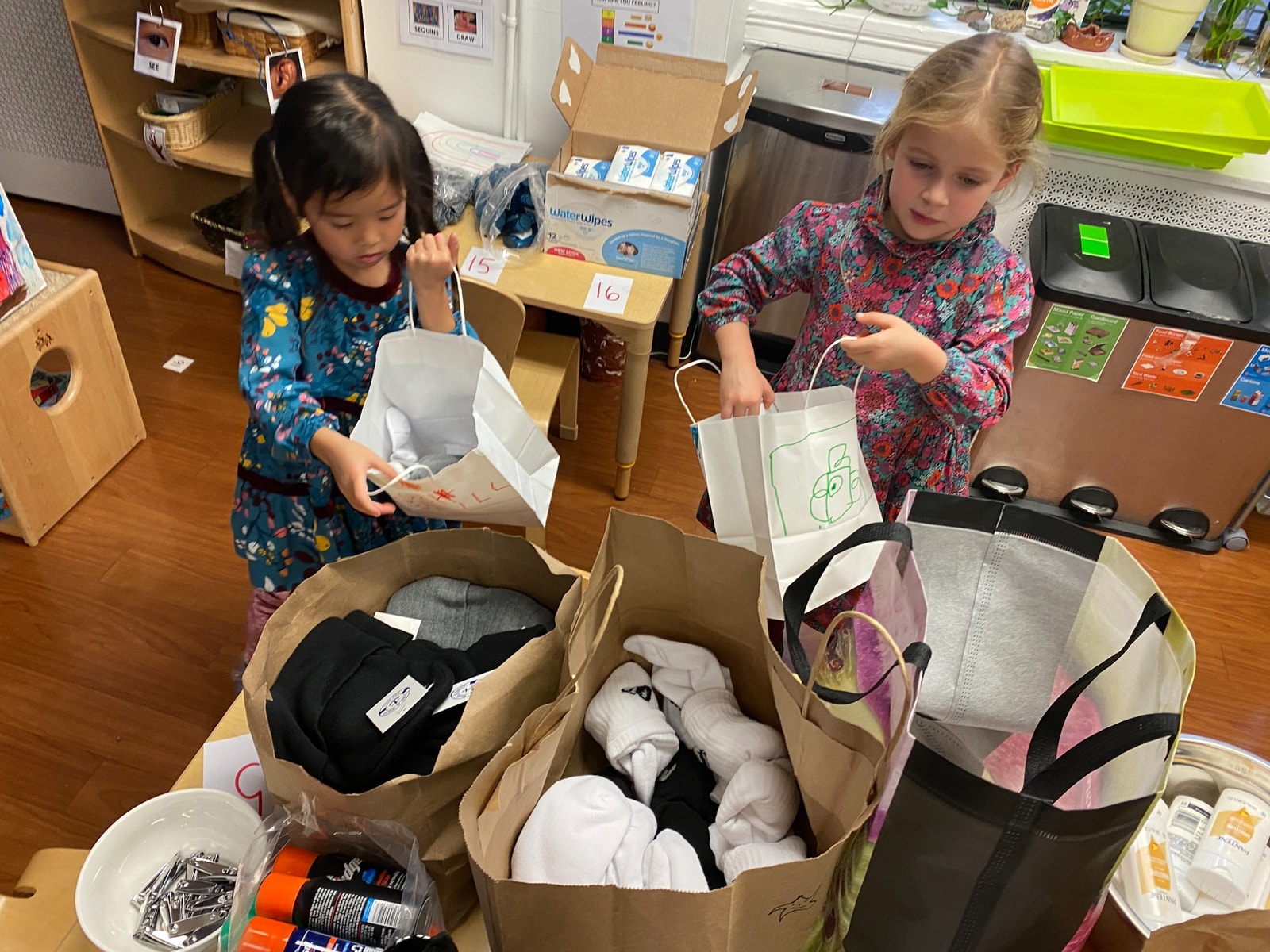

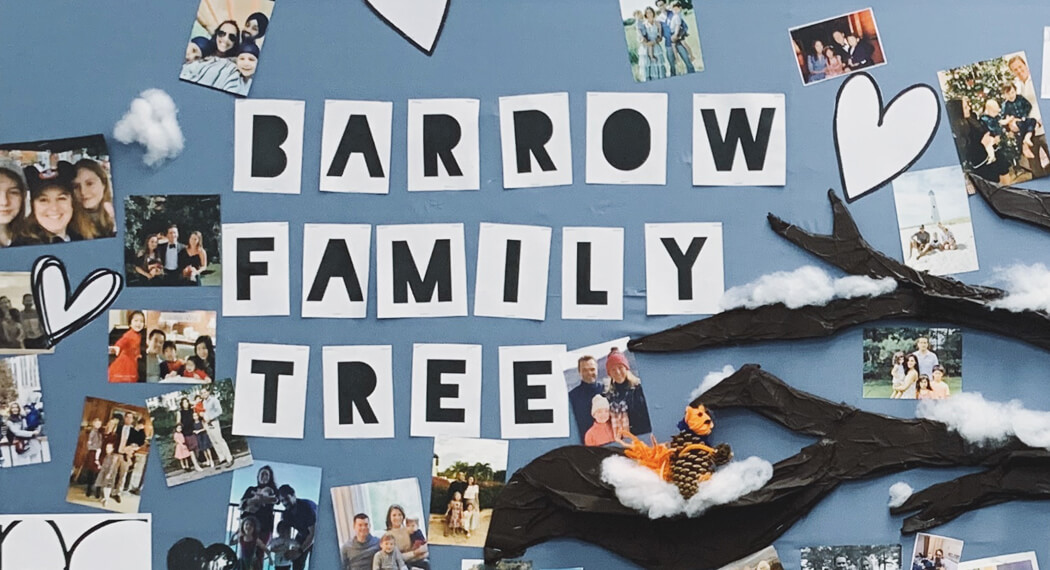

During their initial visits to the Blue Room, children had the opportunity to select a symbol unique to them. No two children share the same symbol. The symbol — like their name — is truly theirs. From the beginning of their time in the classroom, children could identify with something that was special to them and which could be used as a means to represent them. They could look around the space and see various items labeled with their symbol, such as their drinking cup, meeting spot, cubbies, or place on the job chart, and know that these items, like the symbol, belonged to them. The symbols are fairly simple — basic line drawings of common artifacts in the children’s universe — but they convey a clear idea.

But the process doesn’t stop there! Cate notices that all of her classmate Alfons’ items are marked with a book. “That book means ‘Alfons’,” she reasons, and in the Blue Room, she’s right! But Alfons’ items are also marked with letters, different letters — Alfons’ letters. Just as the letters next to the otter mean Cate, the letters next to the book mean Alfons. Soon, Cate can recognize not only her own name in writing but also the names of her classmates. Alongside their symbol, she sees another set of marks and strokes: their names. Seeing these two symbols — one very familiar, the other just starting to make sense — side by side reinforces their connection. Both represent the child to whom they belong. In learning her symbol, Cate learns her name. As she masters her own symbol, she begins to learn those of her classmates. Now, she not only knows which cup is hers but also which cup belongs to each classmate, and she starts associating their names with them.

This seemingly simple act of choosing a symbol to represent oneself helps each child understand, in an increasingly abstract way, how complex things and ideas (and what could be a more complex thing or idea than “self” and “other”?) can be represented symbolically.

Why is this experience so powerful? Because symbolic representation is the foundation upon which reading and writing are built. The written word is based on the idea that marks can form letters, letters can form words, and words can represent things. But this starts with the basic understanding that marks on a page can represent something other than what they physically are. Over time, when they are ready (and many already are!), the children will learn the names of specific letters, their sounds, how to form them, and eventually how to combine them to read and write words. These are rote skills that require practice, repetition, and reinforcement.

More importantly, through this creative and innovative approach, the children are developing a conceptual understanding of symbolic communication — in other words, they are learning how the written word works! And they are doing so because they have been given non-word symbols to bridge the gap from the concrete to the abstract. These seemingly simple symbols are actually facilitating profound learning. In addition to serving other purposes, their key role in supporting emergent literacy may not be immediately obvious to the untrained eye.